It wasn’t the powerful Soviet state machinery in Moscow, but a group of enthusiasts in the Ukrainian metropolis who were the first to commemorate the historic spaceflight of Vostok 1 through philately. This is the other, little-known story of April 12, 1961.

Sometime in the 1990s, during my early years as a spaceflight enthusiast, a friend tried to impress me. He showed me an envelope bearing an unusual cancellation dated April 12, 1961, which he believed to be exceptionally rare and valuable. I wasn’t particularly impressed. “Sometimes a postmark is just a postmark,” I thought, and philately had always been a sideline interest for me. So I forgot about it—until, years later, I happened to pull out nearly the same kind of cover from a box of old letters I had bought for very little money.

That pleasant stroke of luck (not the last, as it would turn out) made me wonder what exactly I had found. And as it soon became clear, behind it lay a story of great interest—not only for astrophilatelists. So, let’s take a closer look.

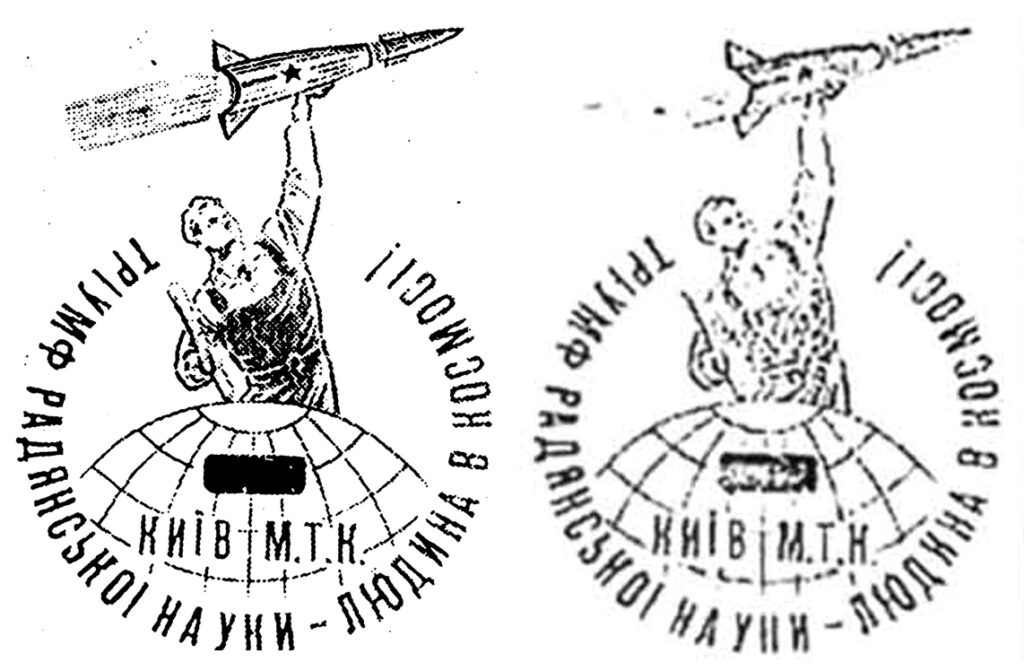

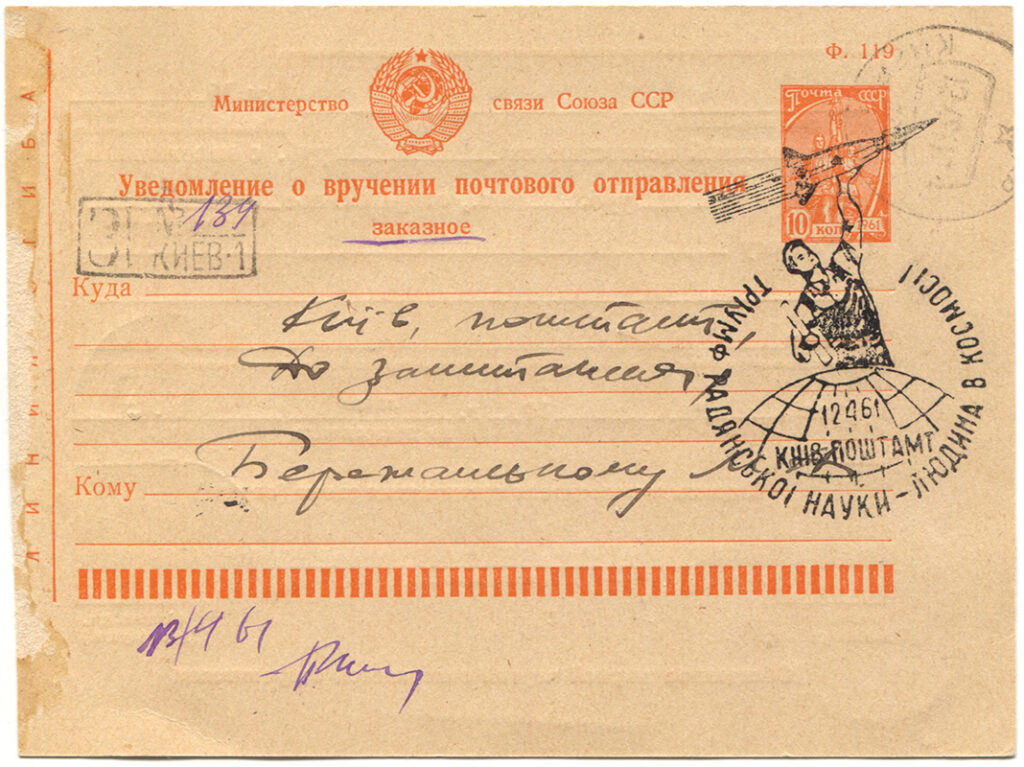

▲ Examples of the Gagarin commemorative postmark, shown here on a blank envelope, along with detailed views of this and other items from my collection.

The postmark depicts a stylized globe with a grid of meridians and parallels, showing the date “12.4.61” and the inscription “Kyiv Post Office.” Above the globe stands a figure in overalls—apparently representing a worker or engineer—holding a rod or perhaps a folding rule in his right hand. With his left, he raises a spacecraft toward the sky. The circular design is surrounded by the inscription “The triumph of Soviet science—man in space!” The lettering is in Cyrillic script, but the language is Ukrainian, not Russian.

What makes this postmark so special?

To finally get to the point, it was the first commemorative cancellation related to Gagarin’s flight ever used in the Soviet Union—and, as we shall see, the only one that was actually applied at a post office on April 12, 1961, the very day of the historic flight.

That fact alone sets it apart even beyond Vostok 1, because the Soviet space program operated under strict secrecy: manned missions were never announced in advance. Moreover, since the Baikonur Cosmodrome had no post office at that time, covers bearing the Kyiv cancellation come closer than anything else to a genuine event cover for the world’s first human spaceflight. In that sense, they hold a truly exceptional historical significance.

Kyiv thus managed to precede Moscow, where the officially sanctioned commemorative cancellations familiar to collectors worldwide were introduced slightly later. Those Moscow postmarks also bore the date “12.IV.1961”—but contrary to what many assumed, they were not used until April 13, 1961.

▲ Examples of the official Moscow Gagarin commemorative postmarks. The left-hand example may have been applied on April 13, 1961, while the right-hand example was probably canceled the following day. Note that two different versions of the postmark were in use, distinguishable by typographic variations—such as the letterforms in “CCCP.”

Compared with the Moscow design, one immediately notices what is missing from the Kyiv version, and what makes it unique in another respect: it does not bear the state designation “USSR.” That inscription was obligatory on official postal cancellations, including special issues celebrating spaceflight. Although there were a few exceptions to this rule in the 1950s, it was no longer omitted thereafter.

This might have been a design oversight by the Soviet Ministry of Communications (MOC), the government authority responsible for all telecommunications and postal services. However, there is strong circumstantial evidence suggesting otherwise: that the Kyiv postmark was not a state production at all.

More Than Just a Club Cachet

The fact that this postmark—used, as shown on my introductory cover, to cancel postage stamps—was actually applied at a postal counter clearly distinguishes it from the many so-called club cachets known from numerous Soviet cities. These were completely unofficial auxiliary handstamps that accompanied a regular dated postmark and appeared—at least superficially—to commemorate April 12, 1961.

▲ Examples from Chelyabinsk and Vinnytsia that may date from April 12, 1961.

Although the auxiliary marking from Vinnytsia bears the inscription “Post Office,” which gives the impression of official origin, such imprints were actually arranged by local philatelic societies creating souvenir items. In most cases, it is impossible to determine when, where, or by whom these club cachets were actually applied, and many examples show evidence of back-dating or even outright forgery. The former was a common practice; the latter became more prevalent once Western collectors entered the market.

▲ Examples from Chelyabinsk and Minsk allegedly dated April 12, 1961. These are back-dated, as the stamps used on them did not yet exist on that day. Curiously, the Chelyabinsk cachet itself changed: the word “Start” became “Flight.”

Such club cachets are decorative—some more so than others—but strictly speaking, they carry little philatelic value. I have often heard collectors dismiss them as “homemade potato stamps.” Yet, if authentic, they hold socio-historical significance: they reveal how contemporaries perceived the importance of the event, and what limited resources they were willing and able to devote to commemorating it—beyond official state efforts. Many fascinating examples of both credible and questionable “Gagarin covers” can be found in the remarkable collection of Efim Sandler.

What Does the Philatelic Literature Say?

The Kyiv postmark has been known since the late 1960s from official Soviet publications, which already sets it apart from other unofficial productions. The earliest reference appears in Evgeny Sashenkov’s Cosmic Age Philately (1969), a standard reference work of its time. It contained an extensive chapter on the philatelic commemoration of Gagarin’s flight. The Kyiv postmark was prominently featured as “the very first ‘Gagarin’ special postmark in the Soviet Union” and illustrated several times.1

When the second edition appeared in 1977—retitled Postal Routes of Cosmonautics—Sashenkov’s once enthusiastic discussion had shrunk to a brief paragraph without illustration. Instead, greater attention was devoted to the official, though in fact later, Moscow commemorative postmark.2

In the meantime, the Kyiv postmark had been included in the semi-official catalog Cosmic Philately, edited in 1970 by Iakov Gurevich and Vladimir Shcherbakov on behalf of the All-Union Society of Philatelists. There it was listed as an official commemorative postmark issued by the Ministry of Communications (as Sashenkov had also implied), but—incorrectly—placed after the Moscow issue. Only a footnote reveals that in Moscow, actual use began on April 13, 1961.3

Most subsequent Western catalogues relied on these Soviet references. Yet the background of the Kyiv postmark remained obscure for a long time, since—unlike other designs—it was almost impossible to obtain.

Much more information emerged only after the end of the Soviet Union, through correspondence with Ukrainian and Russian experts and through renewed attention to the many forgeries that had circulated for years. Particularly noteworthy are the studies by Juri Kwasnikow and Juri Tondrik4, as well as those by Konstantin Zaitsev5 in Weltraum-Philatelie. A concise and up-to-date overview was provided in 2009 by the Moscow astrophilatelist Sergey Poznakhirko in his booklet The Space Age in Philately.6 One should also mention the outstanding systematic research of James Reichman.7 Finally, Umberto Cavallaro helped secure the Kyiv postmark’s place in the broader spaceflight community’s memory through his book The Race to the Moon: “This is the first–and probably only–Soviet space postmark which was actually used on the exact day of the flight.”8

Over time, one conclusion gained widespread acceptance: the postmark had not been produced by a Soviet ministry but had most likely originated from the unexpectedly successful initiative of a philatelic society in Kyiv. On other points, however, expert opinions still differ.

How Did the Postmark Come About?

That anyone managed to introduce a special postmark at a postal counter on the very day of Gagarin’s flight struck Reichman as “a minor miracle or not possible.” Even more remarkable is that the impossible did not happen in Moscow, but in Kyiv. Still, it was not entirely out of the question. When the state news agency TASS announced to the world that the first human had orbited Earth, the time was 10:02 a.m. in both Moscow and Kyiv—the day was far from over.

Naturally, preparation of the postmark must have begun much earlier, and that too seems plausible: the whole world knew about the race for space. Various sources report that the postmark had already been engraved in a Kyiv workshop in January 1961, so that only the date “12.4.61” needed to be inserted on the day itself (Kwasnikow/Tondrik). The production method is described either as zincography (Poznakhirko) or plastic engraving (Zaitsev).

The absence of certain details supports the theory of advance preparation. The postmark design includes no mention of Gagarin’s name, the mission Vostok, or the flight duration—details that would later become standard. Even the spacecraft itself is purely imaginary.

The designer’s name is given in almost all publications as “A. Levin,” but even today not a single other fact about this person is known—not even the first name. The earliest mention appears in Gurevich and Shcherbakov’s catalog, which attributes several later official commemorative postmarks to the same A. Levin, all originating from Kyiv—with one remarkable exception. If this attribution is correct, the same person also designed the official Moscow postmark used from April 13, 1961 onward. That would represent the only direct link between the two “competing” postmarks.

Among the more recent discoveries is the fact that two slightly different versions of the Kyiv postmark were produced. They differed only in one detail: the duplicate version bore the inscription “Київ M.T.K.” instead of “Kyiv Post Office.” The abbreviation stands for the Ukrainian “Міське товариство колекціонерів”—the City Collectors’ Society—commonly referred to in Russian as “Городское общество коллекционеров”, or GOK.

▲ The “MTK” duplicate postmark, illustrated by Kwasnikow/Tondrik (left) and Poznakhirko (right). The two facsimiles are identical. Note the blank cartouche for the date.

It is important to understand that MTK (or GOK) was not the name of a specific organization but a generic designation for local collectors’ associations. The best-known and most influential of these was the MGOK (МГОК) in Moscow. For space-themed material, the Estonian Tartu Club of Collectors (TKK) would later become particularly active.

Why Kyiv omitted any specific organization name remains speculative. Perhaps it was due to the club’s still informal status compared with the already well-established MGOK. The All-Union Society of Philatelists, which formally united such groups under state recognition, would not be founded until 1966.

The existence of the duplicate stamp suggests a clear intent: it could still have been used as a club cachet if official authorization for postal use had not been granted. In that case, it might have become just another private handstamp—soon forgotten. But that did not happen. Only a few test impressions were made with the MTK version before it was either accidentally damaged (according to Kwasnikow/Tondrik) or deliberately destroyed once it was no longer needed (according to Zaitsev).

Either way, the very existence of this duplicate undermines the early literature’s claim—specifically Sashenkov’s—that the postmark was produced by the MOC of the Ukrainian SSR. That attribution also appeared in the first edition of Gurevich/Shcherbakov’s catalog, which assumed that all space-related commemorative postmarks originated from the MOC. Tellingly, this claim was quietly dropped in the second edition of 1979.9

A state origin would have been illogical in any case. Why would the MOC omit the USSR designation, create a parallel MTK version, and prioritize Kyiv over Moscow in honoring Gagarin? Kyiv was not significant for the Soviet space program, and one of Gagarin’s selection criteria was that he was a “true Russian”—not Ukrainian (the first Ukrainian cosmonaut, Pavel Popovich, flew in 1962).

Although, as Reichman notes, the hypothesis cannot be proven with absolute certainty, all evidence points to the Kyiv postmark being the initiative of a collectors’ society. Nonetheless, it could not have been applied at a post office without official approval. Accounts differ on how that approval was obtained. Kwasnikow/Tondrik suggest a joint effort involving a local philatelic club, the Ukrainian SSR Ministry, and the All-Union Ministry in Moscow; Cavallaro, by contrast, writes that permission somehow arrived from Moscow at the last minute.

A more plausible account, described by Zaitsev and Poznakhirko, holds that authorization was granted on the decisive day by the Ukrainian branch of the MOC—possibly after quick confirmation from Moscow. Such local approval would have been both lucky and relatively easy to obtain, since the Ukrainian MOC’s headquarters were located on Kyiv’s Maidan Square—in the very same building as the city’s central post office.

Where and When Was the Postmark Used?

Interestingly, philatelic literature rarely addresses the precise question of where within Kyiv the postmark was applied. By the late 1950s, Kyiv was already a city of over a million inhabitants and naturally had multiple post offices. On official postmarks, the inscription “Post Office” (without further qualifiers) generally referred to the Central Post Office. It is therefore reasonable to assume that this was also the case here—that the mark originated from the Central Post Office of Kyiv, also known as “Kyiv-1.” Incidentally, that same building still serves as the city’s main post office today.

All sources agree that the postmark was indeed used on April 12, 1961, replacing the regular date stamp at the counter. Sashenkov already reported that the commemorative marking was introduced at 5 p.m., and Poznakhirko later added that it remained in use for nearly three hours, presumably until the end of the working day. Only one author provides a differing account: Zaitsev specifically states that the cancellation began at 12:00 noon and lasted only half an hour. Such a brief window would explain the postmark’s relative scarcity, though there seems to be no practical reason for it, and a midday introduction seems less likely than an early-evening debut.

What is clear today is that usage did not end on April 12. Sashenkov’s first edition claimed otherwise, but by his second edition he acknowledged that favor cancellations continued afterward—apparently for several days. Poznakhirko and Reichman both estimate that use probably extended until April 16 or 17, albeit no longer in normal postal operations. What happened to the postmark afterward remains uncertain. Kwasnikow/Tondrik note that its ultimate fate is unknown, while Zaitsev and Cavallaro suggest it may have been transferred to Moscow rather than destroyed.

This uncertainty creates a problem. Unless accompanied by a regular dated postmark (which is usually missing, since the commemorative mark replaced it), there is no reliable way to verify that a given cover was truly canceled on April 12. Nor can the total number of strikes be determined. Even within three hours, as Reichman estimates, there may have been “thousands” of impressions. Thus, while genuine Kyiv covers are not unique, they are decidedly scarcer than those from Moscow, where the official commemorative postmark was used tens of thousands of times.

Moons or Screws, Black or Red?

Closer study reveals more subtle differences among surviving impressions. The first concerns the two thick “dots” appearing beside the globe on some strikes but not others. Early Soviet publications ignored this entirely, but Reichman distinguished between the two types—identical in all other respects—and the consensus today is that both came from the same device.

Explanations have varied over time. Earlier writers viewed the dots as intentional design features—“moons,” perhaps, or symbolic depictions of Earth from opposite perspectives of a cosmonaut—but these interpretations stretch credulity. The design is far too stylized for such cosmological reasoning.

Modern research agrees that the “dots” are technical artifacts, not design elements added (ore removed) subsequently. They were most likely nails or screws fastening the printing plate to its wooden handle. As Kwasnikow/Tondrik and Poznakhirko both describe, the screws had loosened during use, protruding slightly and creating the impression of two “moons.” Once retightened, the marks disappeared. Their occasional appearance thus reflects mechanical issues, not artistic intent—and provides no clue as to when a particular strike was made.

An even more hotly debated question concerns ink color. Sashenkov originally stated that only black and red were used, but later research shows that while these were indeed the main colors (both with and without the “dots”), several unofficial hues also exist: blue, brown, blue-green (Reichman), violet and green (Kwasnikow/Tondrik), light blue and light red (Zaitsev), and even a reported experiment with gold ink by the foreign trade agency Mezhdunarodnaya Kniga (Cavallaro)—perhaps explaining the claim that the postmark was sent to Moscow.

Some experts—such as Kwasnikow/Tondrik and Zaitsev—consider these additional colors forgeries. Reichman, however, observed atypical shades on clearly genuine postal items and suggested that cross-contamination of ink pads might account for the variations. In my opinion, it should also be considered that “new” colors could have resulted from reactions with a solvent that may have been used to clean the postmark before it came into contact with another ink pad. However, all available evidence indicates that black was used most frequently, followed by red.

Some philatelists also ascribe symbolic meaning to the color choice. After Sashenkov’s correction that cancellations continued after April 12, he claimed that all later favor strikes were made in red. This view—repeated by Zaitsev and Cavallaro but disputed by Kwasnikow/Tondrik and Reichman—persists today. There are indeed instances in philately where color variations carry meaning, but in this case, the assumptions are unfounded. Several myths arose over time, including the persistent rumor (see this example) that red ink had been used for about ninety minutes on April 12 to symbolize Gagarin’s orbital flight time.

I have tried unsuccessfully to trace the origin of these claims. What I did find were award-winning astrophilatelic exhibits in which this claim has apparently been passed down for decades—without any verifiable factual basis whatsoever. My assumption is that this is a legend that stems from confusion with another Kyiv postmark—one genuinely applied in red for about two hours, but a year later, on April 12, 1962, the first anniversary of the flight. More on this later.

The Kyiv Commemorative Envelopes

The story of the Kyiv Gagarin postmark would be incomplete without mentioning the two types of commemorative covers on which many of the strikes were applied. These items bring us closer to identifying who was actually responsible for the entire initiative.

▲ Kyiv commemorative covers with special postmarks.

The most striking design on top features a man stepping from Earth—symbolized by one of the Kremlin’s iconic towers—into space, surrounded by the inscription “First Soviet man in space.” The same illustration is repeated in the upper-right corner, where the postage stamp would normally be placed. Along the bottom runs the legend: “On this day, April 12, 1961, Yuri Gagarin flew aboard the Vostok spacecraft as the first human in history into space.” Curiously, all inscriptions are in Russian rather than Ukrainian. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that even the correct spelling of Gagarin’s name (“Гагарин” vs. “Гагарін”) had to be based on the limited information available, primarily the Russian-language TASS special report.

This envelope was mentioned in the same breath as the special postmark from the outset. Sashenkov wrote that “The Ukrainian capital also holds the distinction of issuing an illustrated envelope in honor of the Vostok spacecraft flight.” Yet the inscription along the left margin makes clear that the envelope was issued not by the city but by an organization called “Киевское общество коллекционеров” or Kyiv Collectors’ Society. Translated into Ukrainian: “Київське товариство колекціонерів,” or KTK—that’s right, the Kyiv MTK!

Although details about this society remain obscure, there is no doubt it existed, as evidenced by additional productions. The second Kyiv cover, also mentioning the KTK, bears the Russian inscriptions “April 12, 1961 Flight of the Vostok cosmic spacecraft” and “On board is the citizen of the USSR, Gagarin Y.A.” Its simple line-rocket motif closely echoes the postmark’s design, though it appears unfinished: inside the globe is a blank area, and beneath it an empty frame resembling a banner awaiting text.

Both envelopes list their print runs: 1,000 for the line-rocket version and 600 for the heroic design. The initials “В.З.” identify the artist of the heroic design as Vasily Vasilyevich Zavyalov (1906–1972), a well-known illustrator who designed numerous Soviet stamps—including the very stamps affixed to these covers. According to Sashenkov, Zavyalov had created the artwork months earlier specifically for the “Kyiv philatelists.” He may also have bound them in their choice of language, as Zavyalov was Russian and therefore incorporated a Russian inscription into his motif. It remains unclear who designed the other envelope and where both were reproduced. Their dimensions and paper thickness do not match exactly.

Poznakhirko provides the only additional details: while these envelopes probably date from April 12, 1961, distribution began later—around April 15. If so, a significant portion of the Kyiv postmark’s impressions may likewise have been applied days after the flight. Strictly speaking, these are club covers, produced about a month before the official Soviet postal stationery issued by the MOC. But Kyiv’s collectors were not alone. Similar club covers appeared in several other cities, making it impossible to determine who was first.

▲ Examples of Gagarin club covers from Frunze (Bishkek), Krasnodar, and Perm, each bearing a date stamp of April 12, 1961, along with club cachets. The credibility of these dates is uncertain. Note how the Perm example simulates a commemorative issue through a combination of unrelated markings.

Thus, Kyiv’s true distinction remains the special postmark, not the envelopes themselves. Nevertheless, the envelopes must have been officially approved, as indicated by the “Зак.” (order number) printed on each—proof of authorized printing. However, several philatelic clubs of the period successfully obtained such permissions.

One Year Later

The 1961 Kyiv covers found a fitting continuation one year later, marking the first anniversary of Gagarin’s flight, with another commemorative issue by the Kyiv Collectors’ Society. Once again, the striking Zavyalov design was reused—this time in lower print quality and on inferior paper—accompanied by the inscription: “Anniversary of the spaceflight of Y. A. Gagarin aboard the Vostok spacecraft.” From that year onward, April 12 was celebrated throughout the Soviet Union as Cosmonautics Day.

▲ Kyiv anniversary cover of April 12, 1962, with vignette and special postmark.

The edition comprised 650 copies. The example from my collection bears not only the official commemorative stamp issued for that day but also a vignette depicting Zavyalov’s familiar artwork, overprinted with text referring to the special occasion. As Sashenkov already noted, this was “the first space vignette in the USSR.”

An additional distinction was the special postmark. It was not a local production but part of an MOC issue distributed to 17 cities simultaneously. Yet the Kyiv version held a unique status as it was the only one officially authorized for use in both black and red ink. According to Reichman, the red version was applied “only from 9 am to 11 am, i.e., the flight launch and landing hours of the Gagarin spaceflight exactly one year earlier.“

By this time, however, Kyiv was no longer alone in arranging such special postal events. On April 5, 1962, a week before the anniversary, the MGOK in Moscow opened an astrophilatelic exhibition titled “To the Stars!” and succeeded in securing an official special postmark—remarkably, one that even included the society’s initials, an unprecedented honor. MGOK also produced a commemorative cover for the event by overprinting the official Gagarin postal stationery of the previous year.

▲ Special envelope with postmark of April 5, 1962, for the MGOK exhibition in Moscow.

Since the exhibition in Moscow was dedicated to the Vostok anniversary, MGOK thus managed to release both the first special postmark and the first special cover for Cosmonautics Day—slightly ahead of the actual anniversary. Interestingly, one year later, on April 12, 1963, the Kyiv Collectors’ Society adopted the same method, producing its own commemorative cover by overprinting that year’s official Cosmonautics Day postal stationery. Yet despite the ingenuity of this approach, it never matched the creative level reached in 1961.

▲ Special cover with postmark of April 12, 1963, for the second Cosmonautics Day from Kyiv.

Epilogue: The Forgeries

The Kyiv special postmark also has a less pleasant legacy—forgeries. These have been discussed in detail, particularly by Kwasnikow/Tondrik. One of these forged items even found its way into my own collection. Known as the “package card” variety, it is in fact a notification card—a return receipt that would have been attached to a registered item and returned to the sender as proof of delivery. In other words, it was an early form of acknowledgment of receipt, long before digital tracking. Such cards began appearing among collectors in the early 1980s.

▲ Forged cancellations on a return receipt card. Note the traces of adhesive. While parts of the document may be genuine, the Gagarin cancellations themselves are not.

At first glance, these items appear convincing. Genuine postal covers with the Kyiv postmark are exceedingly rare, so the return-receipt format seemed to prove that the postmark had been used in normal postal operations—and, when combined with a regular date stamp, even on April 12, 1961. Moreover, both red and black inks appear, suggesting a chronological sequence: black first, then red.

Yet there are two fatal flaws. First, there exist dozens—if not hundreds—of nearly identical examples. According to these, from 5 p.m. on April 12, 1961, the same person supposedly mailed identical items at the same Kyiv post office to the same two periodicals, with delivery on April 13 and return to sender on April 14. All known specimens differ only by handwritten numbering.

▲ Detail view of the forged cancellations.

Even more damning are the discrepancies between the forged and genuine impressions. The forged type’s round frame measures 3.9 cm in diameter—one millimeter smaller than the original—and when scaled, the designs do not align. The worker figure lacks detail, the rocket is coarser and blunter, the exhaust plume shorter, and the nozzle less defined. The globe’s curvature is shallower. The lettering is more compressed, shortening the circular legend, and the font itself differs: narrower characters, altered forms (such as the angled “Y” and extended dash). Most strikingly, the numerals in “12.4.61” and the letters in “Киев” show telltale differences—the straight lines of the “4” are curved, and “И” resembles an “H.”

In tracing the origins of this forgery, I encountered a curious clue. The Gurevich/Shcherbakov catalog already illustrated a slightly altered version of the postmark in its first edition (1970): the rocket is held higher, broader in shape, and the letters are rounder and wider, especially noticeable in “B” and “H.” Possibly, an existing impression had been artistically retouched to improve print quality, unintentionally distorting the original.

▲ Direct comparison of the genuine postmark (left) with the altered illustration from Gurevich/Shcherbakov 1970 (center) and the version from the 1979 edition, which matches the forged “return receipt” type. Typical differences are highlighted; all images scaled for comparison.

Matters worsened with the 1979 edition, which—without explanation—replaced the earlier illustration with a new one that is identical to the forged design. It seems likely that the editors had a new drawing made for clarity, unaware that they were reproducing an inaccurate version. This confusion in turn provided an ideal model for counterfeiters, who faithfully copied the erroneous 1979 depiction rather than the genuine 1961 original.

Footnotes

- Сашенков, Евгений Петрович (1969): Почтовые сувениры космической эры. Москва: Издательство «Связь»

- Сашенков, Евгений Петрович (1977): Почтовые дороги космонавтики. 2-е изд., перераб. и доп. Москва: Издательство «Связь»

- Гуревич, Я.Б./Щербаков, В.И.: (1970): Kосмическая филателия. Каталог-справочник. Издательство «Связь»

- Juri Kwasnikow/Juri Tondrik (1994): Wahre Schätze – und ihre Fälschungen, in: Weltraum-Philatelie 138/139, S. 63–73.

- Zaitsev, Konstantin (2001): Fakten, Erkenntnisse + Meinungen zum sowjet. Sonderstempel „12. April 1961 – Kiew“, in: Weltraum-Philatelie 187/188, S. 39-45.

- Познахирко, Сергей (2009): Космическая эра в филателии. Приложение журнал у Филателия No. 3.

- Reichman, James G. (2013): Space-Related Soviet Special Postmarks 1958 to 1991. Philatelic Study Report 2013–1.

- Cavallaro, Umberto (2018): The Race to the Moon Chronicled in Stamps, Postcards, and Postmarks. A Story of Puffery vs. the Pragmatic. Cham: Springer Nature. See also for a short version: Cavallaro, Umberto (2021): Yuri Gagarin: Human Space Exploration Era Turns 60, in: Orbit 128, pp. 20–24.

- Гуревич, Я.Б./Щербаков, В.И. (1979): Kосмическая филателия. Каталог-справочник. 2-е изд. Издательство «Связь».